By Sheryl Ringen for the Preston Times

The Dairy Industry has changed drastically over the years, but one thing that remains the same is the source of the milk we drink and products we consume every week: It still requires a cow.

When you think about it, you realize the importance of milk cows for not only today’s consumer demands, but for the needs of explorers and early settlers too. Each family probably brought at least one milk cow with them as they traveled to settle in Iowa. If not, they would certainly want to acquire one or two after their arrival. With no towns to greet them, pioneer families established a homestead which needed a cow to meet their own milk, cream, butter, and cheese needs, just as they also planted crops and gardens for necessary food. Each homesteader’s goal was to be self-sufficient.

As settlements were established and the population grew, the consumer demand for milk encouraged farmers close to town to bring in and sell milk to households. In those early days, one such milk man was Johannes Moellenhof. His farm was on the south side of School Street up on the hill. His farmhouse sat about where Roger Kilburg’s is now. In Virtus Wilslef’s book titled The Way It Was, he tells of Johannes, or “Honas”, as he became called, driving an old gray, skinny horse hitched to a special, square box of a light delivery wagon with “Moellenhof Dairy” painted on both sides. Virtus describes him as a gruff man with a heavy German accent who was always in a hurry. He would fill a wire basket at the wagon with filled quart milk bottles and walk from house to house replacing empty bottles containing a dime with a full bottle. His horse needed no driver and walked along in the street as Honas made the deliveries. His was the only such business in town at the time. Later, a farmer near town started a route, but it remained small and seemed to have no effect on Moellenhof’s success.

It was 1913 when Amelia Carstensen returned to Preston, a young widow with seven children. Her brother brought a cow from the Kruse farm to put in her back yard for the mild weather. Since she had no barn, the cow was returned for the winter months and for those months, we can assume she relied on home delivery for her milk supply and Honas was probably her milk man.

Years later, Keith Henningsen was the local milk man. He built what in later years became Elmer Yadoff’s bee house on the north end of Mitchell Street. One end was his living quarters, while the opposite end was a large cooler for his milk route.

In 1953, Elmer and Carol Yadoff bought the house and took over the milk route. Milk was delivered to them from Elmwood Dairy of Clinton. Then Elmer and Carol made their deliveries every morning. Carol recalls that all the customers did not have milk boxes for delivery and the people who worked left their door unlocked so they could put the milk directly into their refrigerator. Elmer was in the National Guard then and gone a couple of days each month, so Carol would run the route by herself. They bought a car just for the milk deliveries, so Elmer could work his bees in the afternoon.

Yadoff’s quit the business in 1958 and Keith Anderson took over deliveries for a couple years. His milk was delivered to his parents’ grocery store cooler. Keith’s sister, Nancy Feller, said he would deliver early in the mornings to beat the heat of the day. Following Keith, Loras Budde took over for a few years. They all delivered in both Preston and Spragueville, and they did it without refrigerated vehicles.

Creameries, butter factories and cheese factories were organized in Iowa as early as the 1860’s. The increasing production of hogs in Iowa and the value of skim milk for feeding them, caused the numbers of cheese factories to drop in favor of butter factories, which used only the cream and produced skim milk as a valuable by-product.

In Virtus Wilslef’s book, Cities and Towns of Jackson County, he recalls cream haulers who picked up cans of cream throughout the county with horse drawn wagons. The cream was picked up at the roadside two or three times a week, depending on the season. The farmer’s cans were dumped into large vats furnished by the creamery to haul in the wagons after a cream sample had been taken from each can. These samples would be tested for butterfat at the creamery, as that number determined the price paid. Later motor trucks were used for the hauling and each farmer’s cans were marked and hauled away, to be returned at the next pick-up date. Cream samples were then taken from each can at the creamery. Early cream haulers using motorized trucks that Virtus recalled were: Louis Asmussen and John Steines, of the horse and wagon era , Clarence Jackson, Henry “Butch” Asmussen, Bill Hass, Harry Paup, Leo Driscoll, and Lawrence Kroeger.

The consolidation of Iowa’s dairy industry and increase in the size of dairy cow herds is attributed to the introduction of the hand separator. It was invented in 1885 and became popular in Iowa around 1900. Prior to the separator, farmers, or more likely their wives, skimmed the cream off their cows’ milk and churned their own butter, the excess of which could be taken to town to be sold. With the hand separator, they could now get the maximum amount of cream from their product and haul it to town to sell. This invention decreased labor, improved efficiency and thereby encouraged farmers to increase the size of their herds. Instead of selling their product individually, farmers found they could get better prices by banding together and forming cooperatives. During this time, Iowa dairy farmers were also increasing milk production by feeding corn silage and practicing new scientific feeding methods encouraged by the new Iowa State Agricultural and Experiment Station in Ames. Farmers found by banding together, forming co-operatives, they could assure better prices for producers.

There were two early creameries in Preston: The privately owned John Newman Co. was first, then The Preston Creamery Association began in April of 1899 and was quick to expand. Both creameries were very productive as evidenced in a newspaper article on November 21, 1906 when it was reported that twenty 60-pound tubs of butter were shipped by the Creamery Association, while the Neuman Creamery shipped six 60-pound and nine 40-pound tubs. Neuman eventually sold out to the association.

The association continued to grow and in 1948, the Preston plant produced a total of one million, one hundred and ninety-nine thousand, six hundred and fifty-two pounds of butter from sweet cream.

When the creamery switched to buying milk, instead of cream from the farmers, two large steam-driven cream separators were installed. The steam-engine that power them was also used to churn the cream into butter. The Association later expanded and added cheese curds and pizza cheese to its product.

In 1965 the Farmer’s Co-Op board voted to sell their business to Meinerz Creameries, which, in 1974, became a division of Beatrice Foods Co. Meinerz specialized in pizza cheese and increased capacity so that by 1980 they could process between 15 and 18 million pounds of milk per month working five to six days per week. Milk was shipped from farm to the plant in bulk trucks instead of 10-gallon cans and they could process about 40,000 pounds of milk per hour and produce about 4,000 pounds of cheese per hour. They employed approximately sixty employees and specialized in making mozzarella, provolone, and hard cheeses that were shipped to about forty-three of the states on their own fleet of trucks. Over time, so many local farmers had decreased dairy herds in favor of raising more crops, in January of 1994 Meinerz decided to move all production to their plant in Fredricksburg, Iowa. That marked the end of Preston’s local milk processing plants.

With the declining numbers of dairy farms in the immediate area, a person may think there are fewer cows in Iowa, but that’s not true. Iowa still has over 200,000 milk cows on approximately 1,700 farms. Nationally, Iowa ranks 12th in dairy cow inventory, all according to USDA – NASS, 2019. (As a sidebar, note Iowa is ranked third in the U.S. in its number of milk-producing goats with 214 licensed dairy goat herds and 32,000 milking does in Iowa. It is surpassed only by Wisconsin and California.)

The demand for fluid milk has declined due to the lower number of children in the population and the popularity and availability of other beverages, but the increased demand for milk products has increased to more than make up for that decline. Butter usage has seen a significant increase per capita and another product gaining popularity is yogurt.

From 2014-2019, the price offered for raw milk fell an annualized rate of 6.8 percent during those five years. Now, with milk prices stabilizing and consumer demand for dairy products growing, it is expected to rise steadily through 2024, according to IBIS World Dairy Production, and their projection is an increase of 2.1% this year.

So, while we don’t see pastures filled with dairy cows as we drive through the county, know that they are out there somewhere, probably housed with a thousand others in some large, low, temperature-controlled barn. They are treated well to maintain high production because, although the dairy industry has undergone drastic changes, it still depends on the cows.

We have referenced two of Virtus Wilslef’s books for this article. Copies are available for sale or check out through the Preston Library or contact the Jackson County Historical Society. Virtus had a way of writing that tends to calm the soul, just as his soft voice did in conversation. His memories are sharp, detailed, and it all makes for an enjoyable read.

Anyone wishing to look at more facts and figures regarding Iowa’s dairy industry, or any other Ag related topic, can do so by checking out Iowa State University’s web site. They do a fine job of informing the public of Ag. news.

Cream separators, were instrumental in bringing the dairy industry into the 20th Century. In 1878, the Swede Gustaf DeLaval and the Dane L,C, Nielsen manufactured the first practical centrifugal cream separators. The speed of the spinning bowl caused the heavier milk to rise to the outside of the bowl, while the lighter weight cream went to the middle. It had a spout for each, so fresh, warm milk straight from the cow was poured into the bowl and a bucket placed beneath each spout. Prior to this, milk was allowed to set until it cooled enough that the cream could be skimmed from the top. The danger was that the milk would sour from sitting too long.

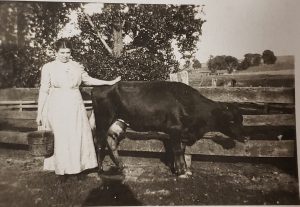

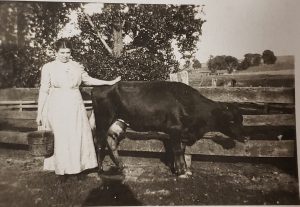

Routine household chores in the early days may have included milking the family cow. Women did not wear long pants at the time, so they did everything in dresses. This photo of Mabel Krumviede’s mother is too good not to share.

There are several different styles of milking parlors popular today. Some have robotic operators, some have the operators in a central location while cows circle around them on a turnstyle, some have cows facing away from the operator, some are sideways, some milk twice per day, some three, but they are all highly mechanized with computers reading their output and keeping track of every mouthful of food each cow eats.

The middle building is the original house/business cooler built by Keith Henningsen. Elmer and Carol Yadoff bought it in 1953. They lived in it and continued the milk deliveries in Preston and Spragueville until 1958.

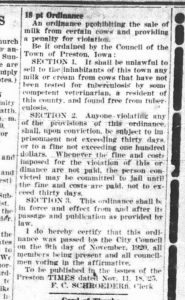

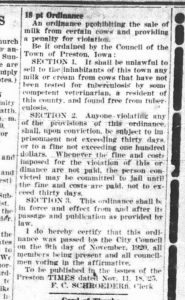

The Preston City Council took action to protect milk consumers from exposure to tubuculosis on November 1, 1920, by passing this ordinance.

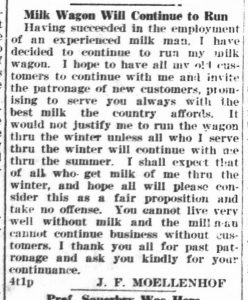

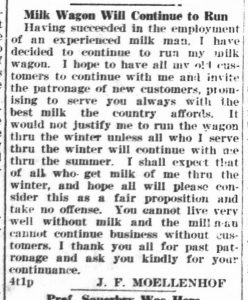

Honas Mollenhof asks his winter customers to continue milk deliveries with him through the summer months. As he put it, “You cannot live well without milk and the milk man cannot continue business without customers.”

One of Henry Kukuck’s Creamery shares issued in 1903 by President Ed Farley and Secretary Samuel McNeil of the Preston Creamery Association. More such shares as well as ledgers and letters from the creamery can be seen at the Old City Hall museum.

Mollenhof quart size milk bottles. Customers would drop a dime in their empties and place them outside their doors if they wanted another.